Learn Music Intervals on Guitar With Fretboard Diagrams

Intervals are the building blocks of music. Think of each interval as a having it’s own personality. It’s your job to get to know each interval and the characteristics of each one, so you know when to use them in a musical context. Intervals will become your friends that you can use to bring out certain feelings or emotions in your music.

This article will give you a solid understanding of every interval. We’ll start with an overview from a theory perspective, then discuss the intervals most relevant to us guitarists.

Why Study Intervals?

I would argue that interval study is the most important of all musical studies: perhaps even more than scales and chords. If you don’t understand intervals, it’s hard to grasp any other topic in music theory. More importantly, intervals produce emotions and feelings in our music. They are the levers that we maneuver to write the music that means something to us from a human perspective.

What Is an Interval?

An interval is distance between two notes in pitch. We can measure an interval in half-steps or semitones. An interval can be played harmonically (at the same time) for chords or melodically (at two different times) for scales, riffs, and licks.

What is an Interval’s “Quality?”

The quality is the way we describe the tonal nature of the interval. Here are the qualities of intervals.

- Minor

- Major

- Perfect

- Diminished

- Augmented

Simple vs. Compound Intervals

A simple interval is anything from a unison up to an octave. Compound intervals are higher than an octave.

Ascending vs. Descending Intervals

Since intervals are measured in half-steps or semitones, they can exist in both ascending and descending directions. A descending interval note is one that has a lower pitch when compared to the root note. Descending intervals are named different than ascending intervals. We give them the inverse name than we would if it were an ascending interval.

Example: The ascending interval of one semitone is a minor second (2nd), but if we descend one semitone it’s known as a major seventh (7th) interval. See the tables and diagrams below to see what I’m referring to. In the tables, there is a column named “Inversion” that lists the descending interval or inversion of the ascending interval. The fretboard diagrams also show some desending intervals for reference. See this Wikipedia article on interval inversion for more information.

Table of Every Simple Interval

| Interval Name | Abbreviation | Distance in Semitones | Inversion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect unison | P1 | 0 | |

| Minor second (2nd) | m2 | 1 | M7 |

| Major second (2nd) | M2 | 2 | m7 |

| Minor third (3rd) | m3 | 3 | M6 |

| Major third (3rd) | M3 | 4 | m6 |

| Perfect 4th | P4 | 5 | P5 |

| Tritone, Augmented fourth (4th), Diminished fifth (5th) | TT | 6 | TT |

| Perfect fifth (5th) | P5 | 7 | P4 |

| Minor sixth (6th) | m6 | 8 | M3 |

| Major sixth (6th) | M6 | 9 | m3 |

| Minor seventh (7th) | m7 | 10 | M2 |

| Major seventh (7th) | M7 | 11 | m2 |

| Perfect octave (8th) | P8 | 12 |

Table of Every Compound Interval

Perfect octave octave is listed for reference.

| Interval Name | Abbreviation | Distance in Semitones | Inversion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect octave (8th) | P8 | 12 | |

| Minor ninth (9th) | m9 | 13 | M7 |

| Major ninth (9th) | M9 | 14 | m7 |

| Minor tenth (10th) | m10 | 15 | M6 |

| Major tenth (10th) | M10 | 16 | m6 |

| Perfect eleventh (11th) | P11 | 17 | P5 |

| Tritave, Augmented eleventh (11th), Diminished twelfth (12th) | TT | 18 | TT |

| Perfect twelfth (12th) | P12 | 19 | P4 |

| Minor thirteenth (13th) | m13 | 20 | M3 |

| Major thirteenth (13th) | M13 | 21 | m3 |

| Minor fourteenth (14th) | m14 | 22 | M2 |

| Major fourteenth (14th) | M14 | 23 | m2 |

| Perfect octave (15th) | P15 | 24 |

Observations From the Interval Tables

- Perfect 8ths and 15ths are the first and second octave from the root note.

- The order of the interval inversions are the exact same, just in opposite order. On the guitar, remember that a note a perfect 5th away is also a perfect 4th away in the opposite direction (see the diagram below, of every interval with roots on the 5th string for examples).

- The tritone interval is always 6 semitones or 3 whole tones away. This is why it has the name “tritone.”

- A 9th is simply a 2nd an octave higher. Same with 3rds to 10th, 6ths to 13ths, etc.

- Inversions of compound intervals are still less than an octave. For a further explanation of this concept, please see this Reddit post.

Minor vs Diminished and Major vs Augmented

You’ve probably noticed that the 4th and 5th intervals do not have a major or minor quality. That’s because the “perfect” intervals can’t be major or minor, only diminished or augmented.

If that confuses you, I don’t blame you. If you’re interested in learning all the technicalities of intervals, just head over to the Wikipedia page on intervals so you can really geek out. Read up until your heart’s content.

You’ll also notice that diminished or augmented notes have slightly higher “unpleasant” sound when you play them with a root note. Perfect example: the tritone interval. It has been historically labled as the “devil’s interval” because of how ominous it sounds.

Intervals On the Guitar

Let’s take our knowledge of intervals we just learned and transfer it to the guitar neck. We’ll start with some diagrams of every interval.

All Intervals On a Single String

Here, every interval up to the 2nd tritone is listed.

All Intervals – Root on 6th String

In this diagram, I have included all intervals within reasonable reach of the root note. Three descending interval inversions are listed for reference and the remaining ascending intervals. Also make note that on the 1st string, above the perfect 15th, I start over with the minor 9th compound interval name.

All Intervals – Root on 5th String

Once again, here are all intervals within reasonable reach when playing from a 5th string root note. More descending intervals (inversions) are listed than the 6th string diagram above. Remember that descending intervals are measured in reverse order. See the table above for clarification.

Chord Naming Conventions

In the diagrams shown up to this point, I have labeled every compound interval with their proper technical name. Make note of the more commonly used names for chords.

- Perfect 8ths and 15ths are just called “octaves”

- 2nds are sometimes called 9ths and vice-versa.

- 10ths are rarely used in chord names. They are just 3rds, up one octave. The 3rd determines the major or minor quality of a chord, so you’ll rarely, if ever see a 3 or 10 in a chord name.

- 4ths are rarely used in chord names, unless the conversation is about quartal harmony (a separate topic). They are often named 11ths, and you’ll see chords with 11.

- 12ths aren’t used in chord names. These are just 5ths, up one or two octaves.

- 13ths are frequently used in chord names. These are 6ths, up one octave.

- 14ths aren’t used in chords names. These are just 7ths, up one or two octaves.

Most Important Intervals for Guitarists To Know

Here are some of the most important shapes and note pairings on the guitar neck to memorize for practical use. These are certainly not all of the note combinations you’ll want to memorize, but it’s a good place to start.

These shapes apply to any two notes on the guitar, anywhere on the neck, as long as the distance from the roots are the same, and the root note is on the same string as indicated in the diagram.

Octaves

Every 12 frets, on the same string, is the distance of one octave. On the same fret, the notes on the 6th and 1st strings are two octaves apart.

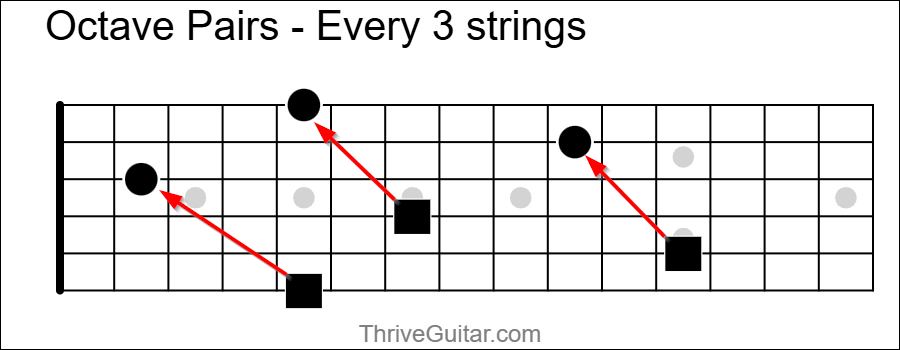

On the 6th and 5th strings, go up 2 frets, and down 2 strings, and you have an octave pairing. This is one of the most useful shapes to know and use. Also note that you must go up 3 frets when the roots are on the 4th and 3rd strings.

The octave parings that span 3 strings are most useful to know in the context of playing chords and arpeggios.

Major Thirds (3rds)

The 3rd interval (whether major or minor) is one of the most impactful note combinations. It is the determining factor in whether a chord, scale, or arpeggio has a major or minor tonality.

Look at the combination below of the root on the 3rd fret, 6th string: doesn’t it look like the start of the G Major chord? Experiment on the guitar by playing the major 3rds then the minor 3rds and see if you can tell a difference in the mood it creates. (I put boxes around some of the combinations where I couldn’t fit arrows in.)

Minor Thirds (3rds)

Perfect Fourths (4ths)

The perfect fourth is a must-know interval, especially the ones with roots on the 6th and 5th strings. They are important to know for chord progressions, which we’ll discuss in other articles.

Perfect Fifths (5ths)

The perfect 5th is another must-know interval, and is one of the most highly used intervals. This combination forms the 5 chord, or “power chord.” It’s also important to know it when we get into the topic of chord progressions.

Major Sevenths (7ths)

These major and minor 7th combinations are very important to know when we start talking about 7th chords. 7th chords are popular in blues and jazz, so if you’re into that, I’m talking to you!

Minor Sevenths (7ths)

Summary

Knowing the intervals very well means knowing music very well. It’s also highly important to memorize all fo the interval combinations on the guitar. Get to know them!

I highly advise you to take this article and grab your guitar. Go through all of the fretboard diagrams and experiment by playing them. Take mental notes of how each one sounds and what kind of mood it creates. As I said earlier, your knowledge of intervals will become your best friend when it comes time to composing and improvising.

I hope you found this useful. If you’d like me to expand on this topic or if you have questions about anything, leave a comment below. Thanks for reading, and have fun with your study of intervals!