Diatonic Chords: How To Write Great Chord Progressions

Are you ready to write songs and chord progression that sound great, even beautiful, to the ear? Diatonic chords unlock this potential. In this article, I’m going to teach you about diatonic harmony and give you the key to writing beautiful, emotionally moving chord progressions and songs. This is one of the most useful and powerful concepts to understand as a musician.

Chord progressions can be a bit confusing if you don’t understand what diatonic chords are and how they function in a song. Why do certain chords sound good together? Why are some chords major and other chords minor, and furthermore, why do they sound good together in certain songs and not others? Let’s learn the answers to those questions!

What are Diatonic Chords?

Diatonic chords are chords that are built only using notes from a particular scale. These chords are typically formed by stacking intervals of thirds on top of each other.

When we build these chords, we end up with a series of various chord qualities. Some major, some minor, some dominant, and sometimes other qualities. The magic happens when we learn those chord qualities and how they relate to the specific scale degrees.

The scale “degree” is the note of the scale the chord is built upon. They are usually indicated using Roman numerals (I, IV, vi, etc.). For instance, the first degree of the Major scale is I. The 2nd degree is ii, an so on. A lowercase numeral represents a minor chord degree. An uppercase numeral represents a major or dominant degree. Dominant degrees will have a 7 after them, like V7.

Diatonic Chords of the Major Scale

For this discussion, let’s use the C Major Scale. The diatonic chords of the C Major Scale are in the order indicated below. For now, we’ll discuss triad chords (chords with 3 notes), then move onto seventh chords later in this article.

| Diatonic (Triad) Chords of the C Major Scale | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Degree | I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | vii |

| Scale Note | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Chord Quality | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Diminished |

| Resulting Chord | C | Dm | Em | F | G | Am | B Dim |

You may be wondering how in the world we end up with these seemingly random chord qualities and in this order. If you play any of those chords in any order, you’ll end up with chord a chord progression that “makes sense” to the ear. Go ahead and try it!

Let’s have a look at the why behind this phenomenon of diatonic chords and how we start using this knowledge to build chord progressions that make sense.

Building Chords By Stacking Thirds

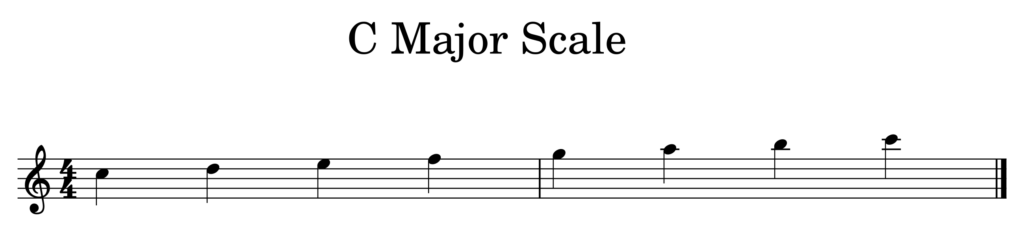

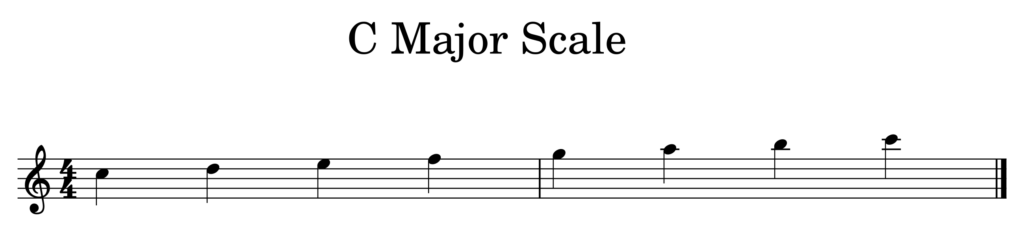

Let’s have a look at the notes of the C Major Scale. I’m using C Major for simplicity’s sake, but this concept applies to any major scale.

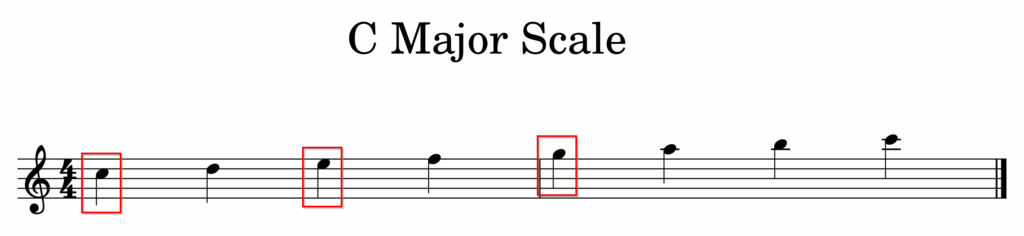

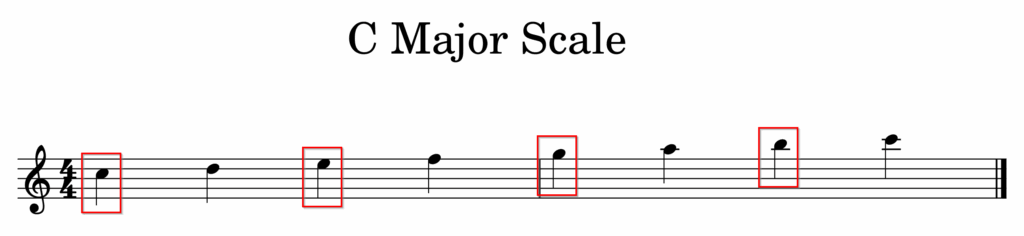

Let’s start with a root note of the C; the first note, and degree, of the scale. Then let’s build a chord using the notes of this scale. We’ll use every other note. Chords are typically built by stacking every other note of a scale on top of each other like this.

If we stack those notes on top of each other and play them all at the same time, we end up with the C Major Chord.

Why is it C Major and not minor, or another type of chord quality? Simple: it follows the chord formula for a major chord. It has intervals of a root, major 3rd, and a perfect 5th. If you need help understanding chord formulas, check out my article on chord types and naming. What happens when we look a the 2nd degree of the scale?

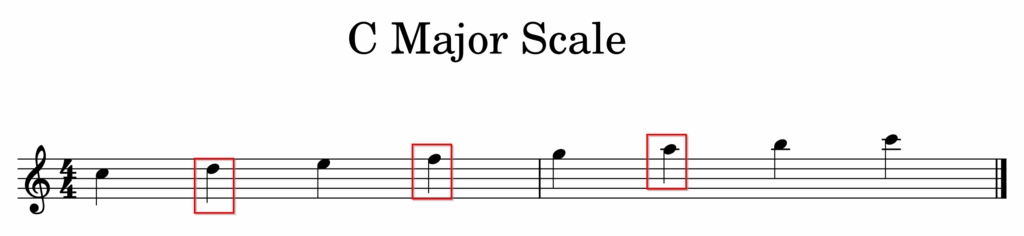

Now we have a D Minor chord. It’s a minor chord because it follows the formula for a minor chord: Root, minor 3rd, perfect 5th.

Can you start to see how this is coming together? We’re simply building chords, by stacking every other note on top of each other, only using notes from the C Major Scale. The resulting chords are “diatonic” to the scale. You can almost think of it as playing the scale, just with notes thrown on top of the scale note.

Building Chord Progressions (and Songs)

What happens when we start playing any of these chords together? THEY ALL MAKE SENSE, MUSICALLY SPEAKING. They will all sound good together. That’s how we can start building songs and writing music of our own!

When I learned this concept, it was like a huge lightbulb and a lot of things started clicking. Now, let’s take a look at some of the most popular chord progressions.

1-4 or I-IV Progression

The I-IV chord combination is one of the most popular in all of music. In our case, we’re talking about a C Major and G Major chord. Try playing those two chords, over and over. Is that not enough for a song? Or at minimum, a good portion of a song?

1-4-5 or I-IV-V Progression

The I-IV-V chord combination is also one of the most popular progressions used in all of popular music. I guarantee you know many songs that use it. In our case, using the key of C Major, it’s the C Major, F Major, and G Major chords.

1-5-6-4 or I-V-iv-IV Progression

The I-V-iv-IV progression is perhaps the most well-known chord progression in most popular music today. Try playing the following chord progression.

C Major — G Major — A Minor — F Major

Sound familiar? This chord progression uses the famous 1-5-6-4 (I-V-vi-IV) chord progression that is used in hundreds (maybe thousands?) of pop, rock, metal, and all kinds of songs in many genres of music.

It is known as the “pop progression” of chords. Just Google the “1564 chord progression” to see how popular this is. You’ll see videos of people playing many different songs by using this chord progression over and over again.

Start Writing Your Own Chord Progressions (and Songs)!

Now that you know the diatonic chords of the key of C Major, it’s time to try and start writing your own chord progressions. Mix and match the orders of the chords too. Don’t think you have to stick to the orders I listed. Just use the table of chords from above. Here it is again for reference.

| Diatonic (Triad) Chords of the C Major Scale | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Degree | I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | vii |

| Scale Note | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Chord Quality | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Diminished |

| Resulting Chord | C | Dm | Em | F | G | Am | B Dim |

There’s no need to stick with the chord progressions I’ve already mentioned above. You can use these to play any chord progression. For example, I think the C — Em — G progression sounds pretty cool. Experiment on your own and start writing your own!

Going Beyond the C Major Scale

Every scale has it’s own set of diatonic chords, but the sequence of chords stays the same, regardless of the scale. Have a look at the table below. These are the diatonic chords of the G Major scale (another popular guitar key).

| Diatonic (Triad) Chords of the G Major Scale | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Degree | I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | vii |

| Scale Note | G | A | B | C | D | E | F# |

| Chord Quality | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Diminished |

| Resulting Chord | G | Am | Bm | C | D | Em | F# Dim |

Notice how the sequence of chord qualities stay the same? The same chord qualities match up to the same scale degrees. The only thing that changes is the root notes of the chords. They match up with the notes of the G Major scale.

You can “transpose” any song to any other scale or “key” as long as you stick with the same diatonic chords of that key.

Playing in “Keys”

What does it mean to play “in a key?” This topic of diatonic chords helps to explain that question. In the examples above, it could be said that we’re playing in the key of C Major or G Major, depending on which scale we’re deriving our chords from.

A song’s key is the degree of a scale that the diatonic chords and progression are centered around. It’s the tonal center of the song and where it will feel like “home” to the ear. You’ll know a song’s key when you feel like it comes to rest on a chord.

Major Keys

When we start or end on a Major chord, and the song has the typical “upbeat” or “happy” sound, we are likely playing in a major key. For example, if we play the diatonic chords of the C Major scale, and the song’s tonal center is based around the C Major chord, we’re playing in the key of C Major.

Minor Keys

What if we start or end a song on a minor chord of that same scale? For example, the A Minor chord? We can then call this the key of A Minor.

One of the most popular rock chord progressions uses the 6-5-4 (vi-V-IV) degrees of the major scale, thus transforming it into a minor key. We call this a minor key since it’s tonal center is around that 6th chord degree of the Major scale.

An example of a chord progression in the key of A minor is Am — F — G

How to Start Using This Knowledge

Hopefully this is all starting to make sense and come together at this point. Again, we’re just building chords using notes from the scales. Some of those chords result in major, minor, or diminished chord qualities.

For any major scale, the sequence of those chord qualities will stay the same. You can take all 12 keys and build diatonic chords based around all of them. This applies to every key!

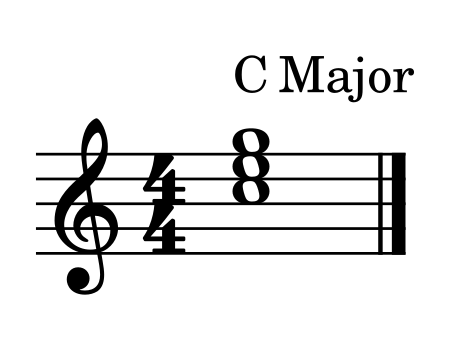

Seventh Chords

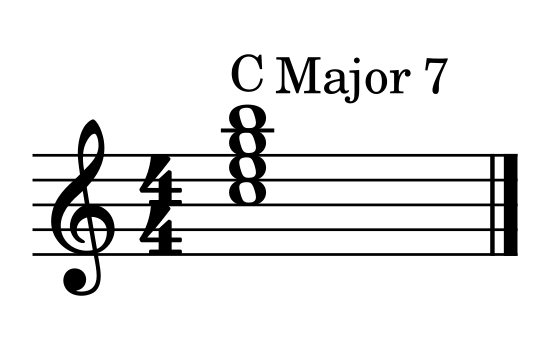

Up to this point, we’ve only discussed triad chords. What happens if we add a 4th note on top of the triad chords we’ve already discussed? We end up with a different set of diatonic chords…seventh chords. They’re called “seventh” chords because they include a major or minor seventh interval.

Once again, here are the notes of the C Major scale

Let’s add a 4th note to the C Major triad chord notes.

We end up with a C Major 7 chord.

When we add that 4th note to the diatonic triads, we end up with the following chord qualities for every scale degree.

| Diatonic (Seventh) Chords of the C Major Scale | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Degree | I | ii | iii | IV | V7 | vi | vii |

| Scale Note | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Chord Quality | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Minor 7 Flat 5 |

| Resulting Chord | CMaj7 | Dm7 | Em7 | FMaj7 | G7 | Am7 | Bm7b5 |

As you can see, we have a whole new set of chords in our arsenal to work with. We’ve introduced major 7, minor 7, dominant, and half-diminished chords into the equation now. Congratulations, you’ve just learned the building blocks of blues and jazz chords. Not to say these chords aren’t used in rock and pop music on occasion, but they are most commonly used in blues and jazz music.

Start experimenting by building chord progressions with these diatonic 7th chords. You may notice some interesting sounds that you never knew you liked. Here’s one example of a beautiful and common jazz chord progression, the 2-5-1 (ii-V7-I).

2-5-1 (ii-V7-I) “Jazz” Chord Progression

The ii-V7-I, 2-5-1 chord progression is the most common in jazz. Try playing the following chords.

Dm7 — G7 — CMaj7

Sounds pretty pleasant doesn’t it? How about we “jazz” it up a bit and add a 13th note onto that G7 to make it a G13, and turn that Dm7 into Dm9?

Dm9 — G13 — CMaj7

These are still diatonic chords, just with some extensions added to them for flavor. This is totally fine, and doesn’t break the “rules” of diatonic harmony. The Dm9 is just a variation of the Dm7 chord. As long as the minor third, and minor seventh notes are there, you still have a minor seventh chord. Just a varation. Same with the G13. It’s still a G7 at the foundation since it has a major third, and minor seventh.

Blues and Jazz Break the Rules, Frequently

To play something “diatonic to” a scale or key, means you’re using from the natural sequence of chords we’ve discussed so far. Does that mean we MUST always play these diatonic chords at all times? Of course not. (But it should probably sound good). Leave it to the rebel blues and jazz musicians to break the rules.

The Blues Chord Progression

The blues uses a I7-IV7-IV7 chord progression. That means a dominant 1, 4, and 5 chord. For example, blues in the key of C would be C7, F7, and G7. Do these chords make diatonic sense? No. Do they still sound good? Yes.

Jazz Examples

Another example of this is the jazz tune “Take the A Train.” The song starts with a C Major 6th chord, then moves to a D7 chord. Right at the beginning of the song, it’s breaking the “rules.”

These things left me scratching my head when I first learned about diatonic harmony. What’s the takeaway from this? Music doesn’t always have to make sense from a theory perspective to sound good!

There are countless jazz tunes I have studied and wondered; “How can they do that? The theory doesn’t make sense!” Then I realized, it doesn’t always have to. The only measuring stick is your ear. It’s up to you to determine if you like music that breaks a theory rule here and there. Many people do, including myself.

Summary

Now that you understand what diatonic chords are and what diatonic harmony is all about, you hold a powerful set of knowledge you can put to use as you please.

You now know how to piece together a series of chords that not only make sense but can sound very beautiful to the ear. Not to mention the heart.