Guitar Chords Explained: A Guide to Chord Types and Naming

Do guitar chords confuse you? Their names, their nicknames, their qualities, and the theory behind it all? Let’s remove the confusion! In this article, I’ll explain the types of chords we play physically with our fingers, and then we’ll dig into the theory behind them all, so you can understand what it all means.

What is a Chord?

A chord is two or more notes played at the same time (harmonically). This is the opposite of a melody, when the notes are played separately, over a span of time. Chords form the foundation of rhythym guitar playing and accompaniment. Learning to play a few chords is a great first step for beginner guitarists.

When you learn how to play a progression of chords, you’re learning how to build the foundation of a song. Having the ability to play chord progressions and the rhythm portion of your favorite songs is a very rewarding experience.

Where to Begin With Chords

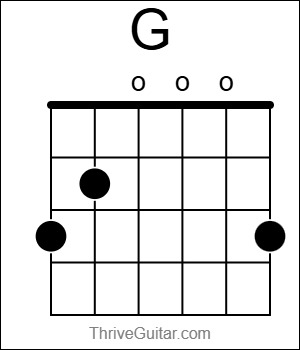

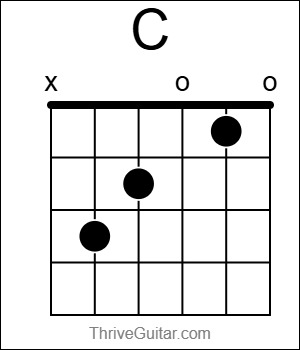

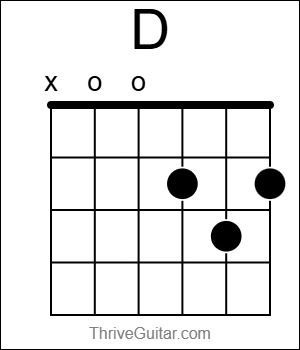

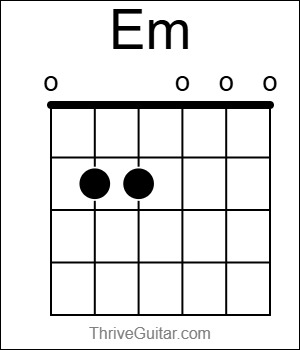

Most beginners usuallly start by learning the “open” chords. It’s how I started. My first real accomplishment on the guitar was learning how to play the open G, C, D, and Em chords. This group of chords allowed me to play a lot of songs.

The G, C, D, and Em chords happen to be the I, IV, V, and VI chords of the G Major key. What does it mean to play in a key? We’ll cover that later.

Types Of Chords Played On The Guitar

Let’s start from a practical standpoint by discussing the types of chords we play on the guitar. Then we’ll get into some theory.

Open Chords

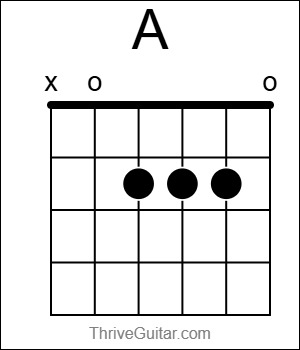

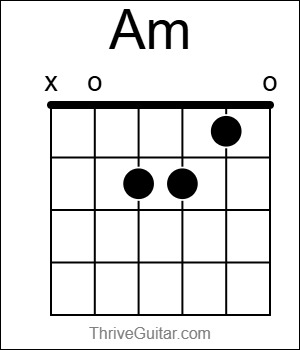

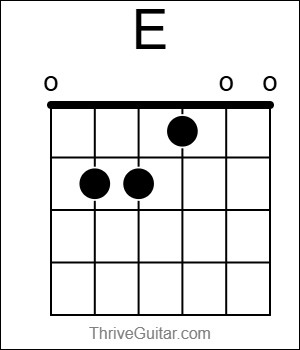

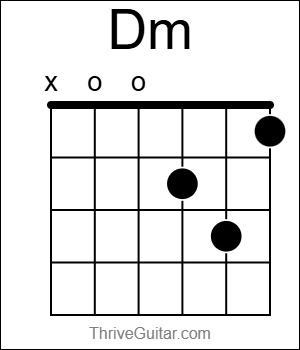

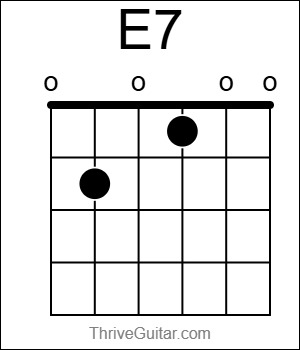

First, we have the open chords. They’re called open chords because they utilize the open guitar strings. They’re played on the first three frets of the guitar, close to the nut.

As I mentioned, these are usually the first chords you’ll learn as a beginner. Maybe you know a few of them already, maybe not. Don’t worry, I’ll show you the most common open chords you should know how to play right here in this article.

Let’s start with the four chords I learned as a beginner: G, C, D, and Em.

If you don’t know how to read chord diagrams, check out my article on that.

I won’t torture you by making you play Hang Down Your Head Tom Dooley, like my first instructional VCR tape did, but these are a great starting point. Here are some other open chord shapes you should learn.

Now that you know all about the essential open chords, let’s talk about how to “transpose” the key you’re playing in by using a capo.

Playing With a Capo

Want to know a “hack” to playing open chords in any key, up and down the neck? Use a capo! It’s basically a clamp that frets all 6 strings for you, effectively moving the nut anywhere on the neck.

For example, let’s say you know how to play an open G chord. Place the capo on the 3rd fret and play that same G shape. it now becomes a Bb chord. Voila! Now you can play all the open chord shapes in the key of Bb Major

I’ll admit that for a while, I thought of using a capo as “cheating.” After all, if you know how to play the barre chords anywhere on the neck, only less experienced newbies need capos, right? NO. Here’s why I don’t think that anymore.

When I was playing in the band at my church, we had singers that sung in keys that weren’t played in “guitar-friendly” keys (G, C, D, A, etc.). Sometimes we needed to transpose the song to another key. But so what, right? I know how to play barre chords all over the neck, so I can play in any key, without problems! I didn’t need no capo! The thing is, after about long 5, 7, sometimes even 10 minute worship songs that involve continuous, non-stop barring of strings, it sets your forearm muscles are on fire!

Eventually, the capo just made more sense. Even if you can play barre chords without problems, the capo helps save your hand and wrist from unnecessary torture, especially in live performance. Want a forearm workout at home? Sure, go ahead and play those barre chords for an hour straight. But if you want to survive the live set and still have a functional left-hand, use a capo!

Barre (Bar) Chords

Once you’ve got the open chords down, you’ll want to learn barre chords. Technically they’re spelled “barre” chords, but I’m just going to call them “bar” chords from now on. Sound good? Technically, we are “barring” the fret with our fingers anyway.

Bar chords require you to press multiple strings down (to “bar”) with one finger, usually your index, across a fret. For example, the F major chord requires you to bar the 1st fret and then place your other fingers in the correct shape.

Most beginners struggle with bar chords at first, but fear not! Eventually, with practice and building the right muscle strength, it’ll become second nature. I remember seeing bar chord diagrams as a beginner and thinking “no way I’ll never be able to play that thing.” I can plaly them easily now, and you will too.

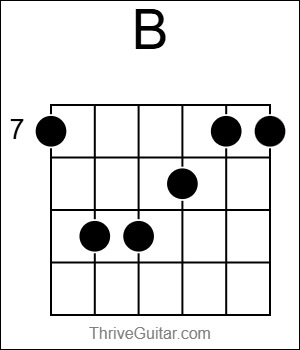

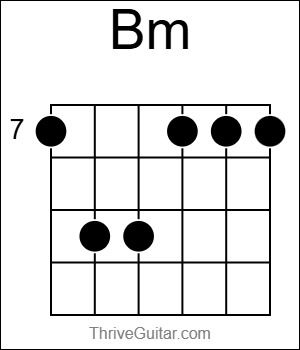

The great thing about bar chords is you can play them anywhere on the neck. That’s huge! No longer are you limited to the first 3 frets by open chords. Yes, you can still use a capo, but sometimes you simply need to know how to play these bar chords.

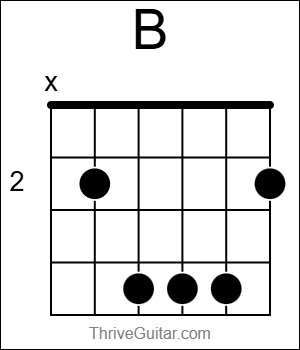

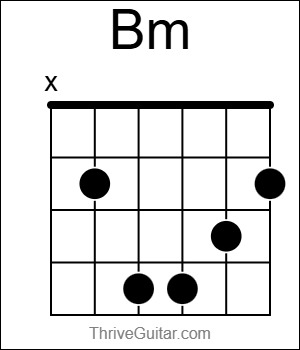

Here are some diagrams of the popular “triad” bar chord shapes in major and minor versions. I’m going to use B as the root note for these because it’s not a guitar-friendly key. These chords shapes have roots on the 6th and 5th strings.

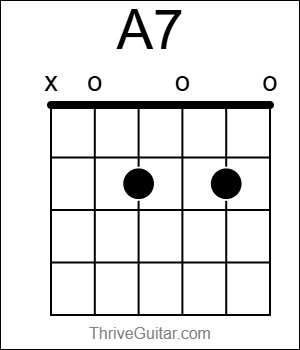

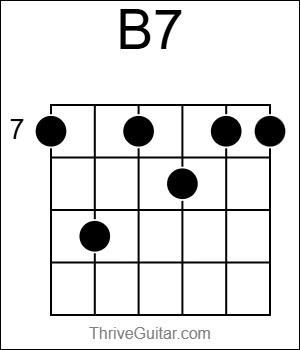

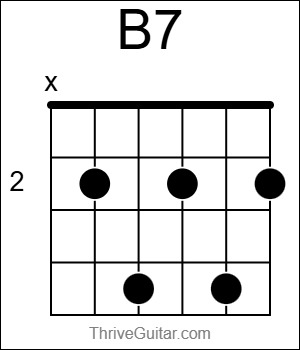

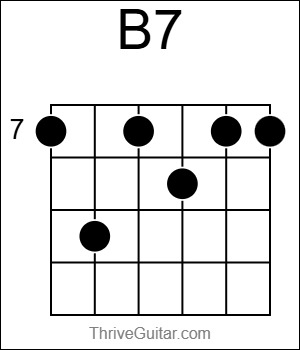

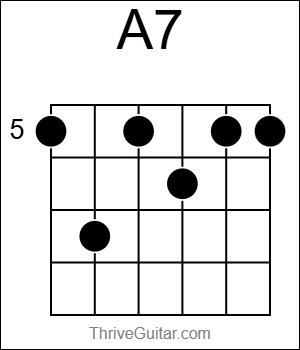

Here are a couple of the “dominant” bar chord shapes.

In full discolosure, all of these barre chords are tricky to learn. But you’ll learn them well over time. Be patient with yourself. The major and minor triad chords are very useful, obviously, but the dominant, chords are especially fun to play and useful for playing blues and jazz.

Combine this knowledge with your understanding of notes on the 5th and 6th strings, and you’ll have everything you need to play almost any chord. For example, see how a B7 chord shape can become an A7 chord if we move down two frets?

This applies anywhere on the neck. Now you know how to play any of these chords with any root note.

Power Chords (5 Chords)

Power chords are the bread and butter of rock and metal music! They deliver that iconic powerful sound and are usually played with distortion to pack extra punch.

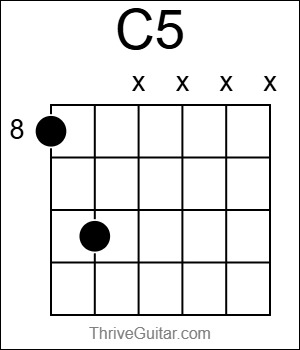

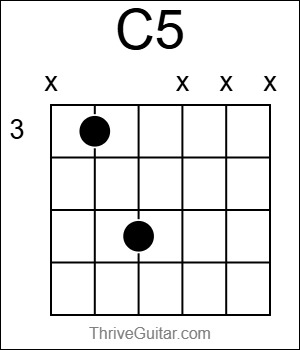

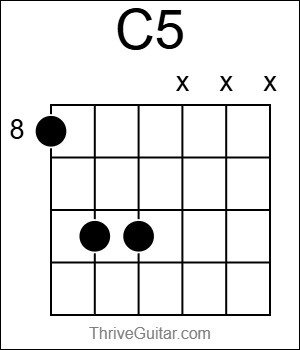

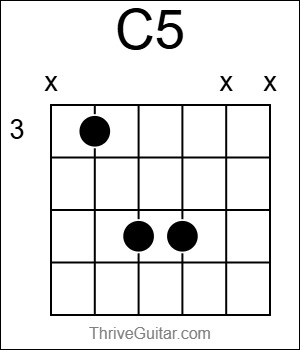

Power chords are often labeled A5, B5, etc., and are built on the root and perfect fifth intervals, sometimes with the octave added. They’re usually played on the 6th and 5th strings (and occasionally the 4th). Here’s are a couple of C5 examples with the root and 5th notes.

You can also play it with the octave note for a fuller sound.

Drop D Power Chords

Want an easier way to play power chords? Try Drop D tuning.

In Drop D tuning, you tune your 6th string down a whole step (E to D). This lets you play power chords by simply barring the 6th, 5th, and 4th strings across one fret.

Just remember: since the tuning has changed, your root notes on the 6th string have shifted. For example, in standard tuning, B5 is at the 7th fret, but in Drop D, you’d play it at the 9th.

“Shell” Chords

After learning open and bar chords, you’ll eventually want to explore shell chords. These chords are made up of only 2 or 3 essential notes, including the root, 3rd and 7th intervals. Sometimes even the root is even left out.

These are common in jazz and blues and are great for accompanying, or “comping,” for other musicians while they are soloing or improvising. They may not be the easiest to understand at first, but once you do, they are incredibly useful and perhaps more practical than full bar chords. We’ll discuss these in other articles.

Chord Naming and Qualities

We’ve discussed the various chord types we play on the guitar, physically with our fingers. Now, let’s talk about some theory behind those guitar chords and their names.

Every chord name starts with a root note (A, B, C, etc.), followed by letters or numbers that describe the chord quality. That’s how we distinguish between something like G major and G minor 7b5. Speaking of seventh chords, let’s talk about the differences between triad chords and seventh chords.

Triads vs. Seventh Chords

If you see a chord labled major or minor, you can safely assume it’s a triad chord. Triads consist of three notes: the root, 3rd, and 5th. Seventh chords add a 7th interval on top of the triad. Sometimes the 7th is a major 7th interval, sometimes its a minor 7th interval. This affects the name of the chord.

This can all get bit confusing. Let’s break down the different qualities and names. Here is a rundown of each chord quality and the differences between them. You can think of these as a set of “formulas” that form the foundation of the chords.

Major Chords

- Notes: Root, Major 3rd, Perfect 5th

- Labeled as: G, A, C (just the letter)

- Sound: Happy, bright

Minor Chords

- Notes: Root, Minor 3rd, Perfect 5th

- Labeled as: Am, Em, Dm

- Sound: Sad, serious

Major 7th Chords

- Notes: Major triad + Major 7th

- Labeled as: Gmaj7, Cmaj7

- Sound: Smooth, jazzy, mellow

Add a 9th for a Major 9 chord (e.g., Gmaj9), or a 13th for a Major 13 chord.

Minor 7th Chords

- Notes: Minor triad + Minor 7th

- Labeled as: Am7, Dm7

- Sound: Dreary, jazzy, sad

Add a 9th to make a minor 9 chord (e.g., Am9).

Dominant 7th Chords

- Notes: Major triad + Minor 7th

- Labeled as: G7, A7

- Sound: Bluesy, sassy, slightly tense

These are called “dominant” because they’re built from the 5th degree of the major scale. The 5th degree is known as the “dominant” degree.

Diminished Chords

- Notes: Minor 3rd + Diminished 5th (tritone)

- Labeled as: Bdim, C°

- Sound: Tense, unresolved

Augmented Chords

- Notes: Major 3rd + Augmented 5th

- Labeled as: C+, Gaug

- Sound: Uneasy, dramatic

Half-Diminished Chords

- Notes: Diminished triad + Minor 7th

- Labeled as: Bm7♭5 or Bø

- Sound: Mysterious, jazz-friendly

What Are Diatonic Chords?

This is an important topic that I want to touch on before we end our chord discussion. You may have heard of “diatonic chords.” So what are they? Diatonic chords are chords built using only the notes of a particular scale. They are essential to understand when it comes to playing chord progressions and playing in a particular key.

For example, chords in the key of G major are built from only the notes in the G major scale. We create them by stacking 3rd intervals on top of other scale tones.

These chords help form common chord progressions that sound familiar and pleasant. I’ll dive deeper into diatonic harmony in another article. It’s one of the most useful concepts to know as a musician!

Summary

All of the concepts in this article were confusing to me when I started trying to advance from the beginner to intermediate level of guitar playing. I would have loved a guide like this when I was starting out playing the guitar. Hopefully this overview has been helpful for you. You may even want to come back to this article for reference sake. These concepts are very important.